Review

HJOG 2025, 24 (3), 170-181| doi: 10.33574/hjog.0596

Vasilios Pergialiotis, Maria Fanaki, Antonia Varthaliti, Vasilios Lygizos, Dimitrios Haidopoulos, Nikolaos Thomakos

First Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, “Alexandra” General Hospital, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece.

Correspondence: Vasilios Pergialiotis, MD, MSc, PhD, 6, Danaidon str., Halandri 15232 – Greece, e-mail: pergialiotis@yahoo.com

Abstract

Background: Vulvar cancer is an uncommon gynecologic malignancy that is usually manifested in older ages which have several comorbidities. Frail patients pose a significant subgroup in gynecologic oncology as frailty may affect treatment plans and result in significant reduction of survival outcomes. In the present systematic review we summarize current evidence focusing on the impact of frailty in vulvar cancer patients.

Methods: We systematically searched the international literature using the Medline, Scopus, Clinicaltrials.gov, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials CENTRAL and Google Scholar until March 2025. Prospective and retrospective studies were considered eligible for inclusion.

Results: Six articles were included in the present systematic review that involved 2,785 patients. Significant heterogeneity was noted as well as methodological issues that were mainly based on the absence of control group in the majority of included studies. The meta-analysis indicated that non-frail patients had increased chances of survival (HR 2.40, 95% CI 1.27, 4.54) whereas the rate of complications was particularly different among studies included, ranging between 6 and 79% of cases (OR 0.26, 95% CI 0.10, 0.51). The actual impact of frailty on treatment decisions was particularly underreported, whereas none of the studies included correlated treatment decisions with survival outcomes.

Conclusion: Current evidence focusing on the impact of frailty on survival outcomes and treatment plans in vulvar cancer patients is extremely scarce. Considering that this group of patients involves older patients, more research is needed to evaluate the optimal management of these cases.

Keywords: Vulvar cancer, frailty, comorbidities, survival, meta-analysis

Introduction

Vulvar cancer is an uncommon malignancy with an annual incidence of 2.6 per 100,000 women per year [1]. It is the fourth most common gynecologic malignancy [2], and is commonly seen in elderly patients [3]. The presence of various comorbidities is frequently encountered among vulvar cancer patients, and these have a direct impact on perioperative outcomes as well as the course of the disease in terms of survival outcomes [4, 5].

The gold standard for the treatment of patients that suffer from vulvar cancer is surgery [6]. Radical excision of the disease, ensuring negative surgical margins is the cornerstone of treatment and in cases where the depth of invasion exceeds that exceeds 1mm, routine inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy is required [6]. Less radical therapeutic methods have been available in recent decades with the role of sentinel lymph node being a potential novel approach.

Wound complications are frequent among vulvar cancer patients as microvascular dysfunction, which is manifested in a significant proportion of those, has a detrimental effect on wound healing [7]. Frailty is another significant component in this group of patients that may significantly deviate treatment plans from optimal procedures [8] and directly affects perioperative outcomes. Several tools have been developed to help identify the severity of frailty among cancer patients and the modified frailty index, risk analysis index, however it is important to stress out that the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) as well as the American Society of Clinical Oncology underline the importance of several other tools that explicitly target specific domains of frailty such as the functional status in terms of autonomy and mobility, the cognitive status, the polypharmacy status etc [9-11]. To date, the impact of frailty on treatment decisions of patients suffering from vulvar cancer as well as survival outcomes remains obscure as relevant data remains scarce. In the present systematic review we opted to summarize the available evidence, discuss the gaps in knowledge and provide directions for further research.

Methods

The systematic review was pre-registered in PROSPERO (International prospective register of systematic reviews) (Registration number: CRD420250656355) and was conducted taking in mind the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [12]. All data were retrieved from studies that were published in the international literature, therefore, patient consent and institutional review board approval were waived.

Eligibility criteria, information sources, search strategy

The eligibility criteria for the inclusion of studies were predetermined. All studies that examined the impact of frailty on treatment decisions and survival outcomes of patients with vulvar carcinoma were considered as potentially eligible for inclusion, provided that the outcomes of interest were present. We opted to include all available data to the scarcity of available evidence, irrespective of whether the reported cohorts provided a control group or not. Case reports and studies on preclinical models were excluded from the present meta-analysis.

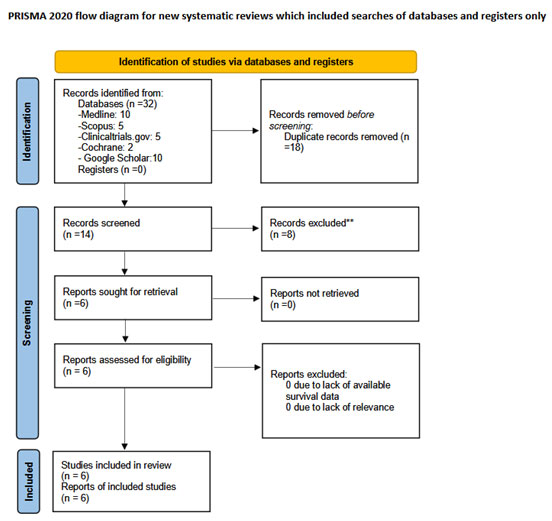

We used the Medline (1966–2024), Scopus (2004–2024), Clinicaltrials.gov (2008–2024), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials CENTRAL (1999-2024) and Google Scholar (2004-2024) databases in our primary search along with the reference lists of electronically retrieved full-text papers for articles published in the Latin alphabet, regardless of the actual language that was used. A decision to translate languages other than English, French, German, Italian and Spanish with online translating tools was taken before the onset of the search. The date of our last search was set as March 10, 2024. Our search strategy included the text words “frailty OR frail AND vulvar cancer” and is briefly presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Search plot diagram.

Study selection

The retrieval of eligible studies was performed in three consecutive stages. Firstly, deduplication of retrieved articles was performed using the Rayyan software. This step was followed by manual screening of titles and abstracts of all electronic articles that remained by two authors (MF and AV) to evaluate their eligibility. In the final step of the study selection process, studies that were considered potentially eligible were selected for review of the full text. Discrepancies that arose following this stage were resolved by consensus from all authors.

Data extraction

Outcome measures were predefined during the design of the present systematic review. Data extraction was performed using a modified data form that was based in Cochrane`s data collection form for intervention reviews for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-RCTs. The primary outcome of our study was the evaluation of differences in survival rates (overall survival – OS and progression free survival – PFS) of vulvar cancer patients that were or were not assessed as severely compromised (frail). Treatment decisions (such as avoidance of radical surgery, avoidance of postoperative adjuvant therapy or combinations of adjuvant therapy) were also considered as a secondary outcome.

Assessment of risk of bias

The methodological quality of included observational studies was performed by two authors (MF and VP) using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) score that assesses the risk of bias in observational studies by evaluating the selection of the study groups (maximum rating 4 points), the comparability of the groups (maximum rating 2 points – 1 for comparable histological subtypes and another one for the actual stage of the disease at pathology analysis) and the outcome of interest (which was predefined as a minimum of 3-years median follow-up (indicated either by the authors or by an interval ≥ 3 years between the last patient recruitment and publication of the article)) (maximum rating 3 points) [13]. In cases of disagreement, a third reviewer (AV) was consulted to resolve discrepancies through discussion and consensus.

Data synthesis

Statistical meta-analysis was performed with RStudio using the meta function (RStudio Team (2015). RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, Inc., Boston, MA URL http://www.rstudio.com/). Statistical heterogeneity was not considered during the evaluation of the appropriate model (fixed effects or random effects) of statistical analysis as the considerable methodological heterogeneity of observational studies does not permit the assumption of comparable effect sizes among studies included in meta-analysis [14]. To limit the effect of potential confounders, including stage of the disease, grade of differentiation and other variables, including lymphovascular space involvement and molecular profile of tumors, outcomes from multivariate models were preferred over aggregated results from univariate analyses. Confidence intervals were set at 95%. We calculated pooled hazards ratio (HR) of survival as well as odds ratios (OR) of treatment decisions as well as their respective 95% confidence intervals (CI) with the Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman instead of the traditional Dersimonian-Laird random effects model analysis (REM). We opted to use this model as recent research indicates its superiority compared to the Dersimonian-Laird model in terms of accounting for the heterogeneity of included observational studies that are expected to differ considerably in their methodology [15].

During the design of this systematic review, we considered the Egger`s test as a statistical method to evaluate the possibility of publication bias. This method represents a linear regression analysis that takes into account the intervention effect estimates and their standard errors which are weighted by their inverse variance [16]. It is considered important only when substantial evidence is present and a pre-requisite of at least 10 studies was predetermined as a minimum cut-off per investigated outcome to ensure appropriate credibility of retrieved findings [17]. In our study the limited amount of data rendered impossible the evaluation of publication bias as well as other analyses that are based on substantial amount of data, including Rücker’s Limit Meta-Analysis that permits the evaluation of small study effects in the meta-analytic pooled effect as well as p-curve analysis which helps investigate the truthfulness of aggregate results of included studies and exclude the possibility of data manipulation (p-hacking).

Results

Overall, 6 articles were included in the present systematic review that involved 2,785 patients [4, 18-22]. The search strategy is summarized in Figure 1. The methodological characteristics of included studies are presented in Table 1 and denote the significant discrepancy in terms of patients’ characteristics. Table 2 indicates the differences in histological parameters, and overall management of included patients as well as postoperative complications. The methodological assessment revealed significant flaws that were mainly the result of the absence or the absence of definition of a control group (Table 3). Other than that, several studies did not evaluate the primary outcome, namely survival outcomes an effect that significantly reduced the importance of the meta-analysis.

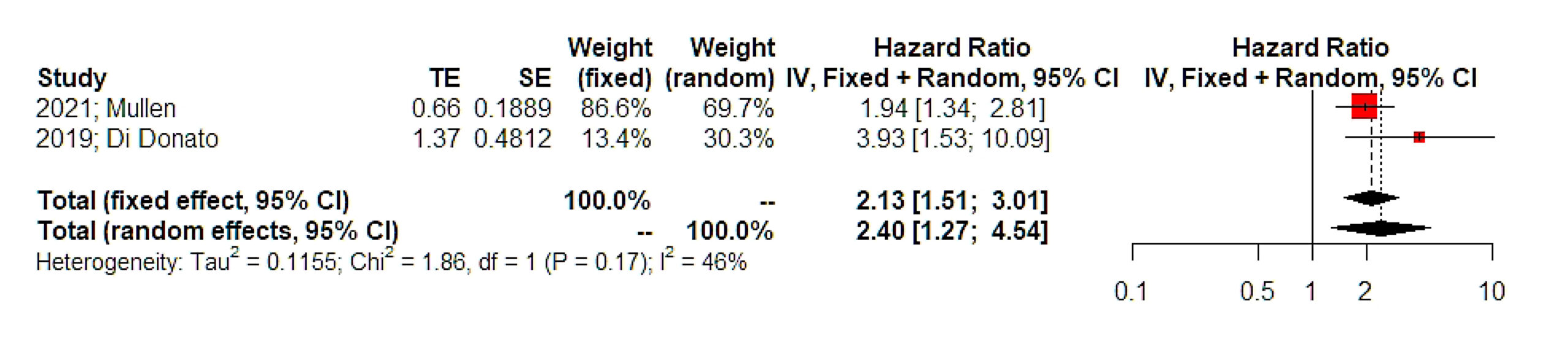

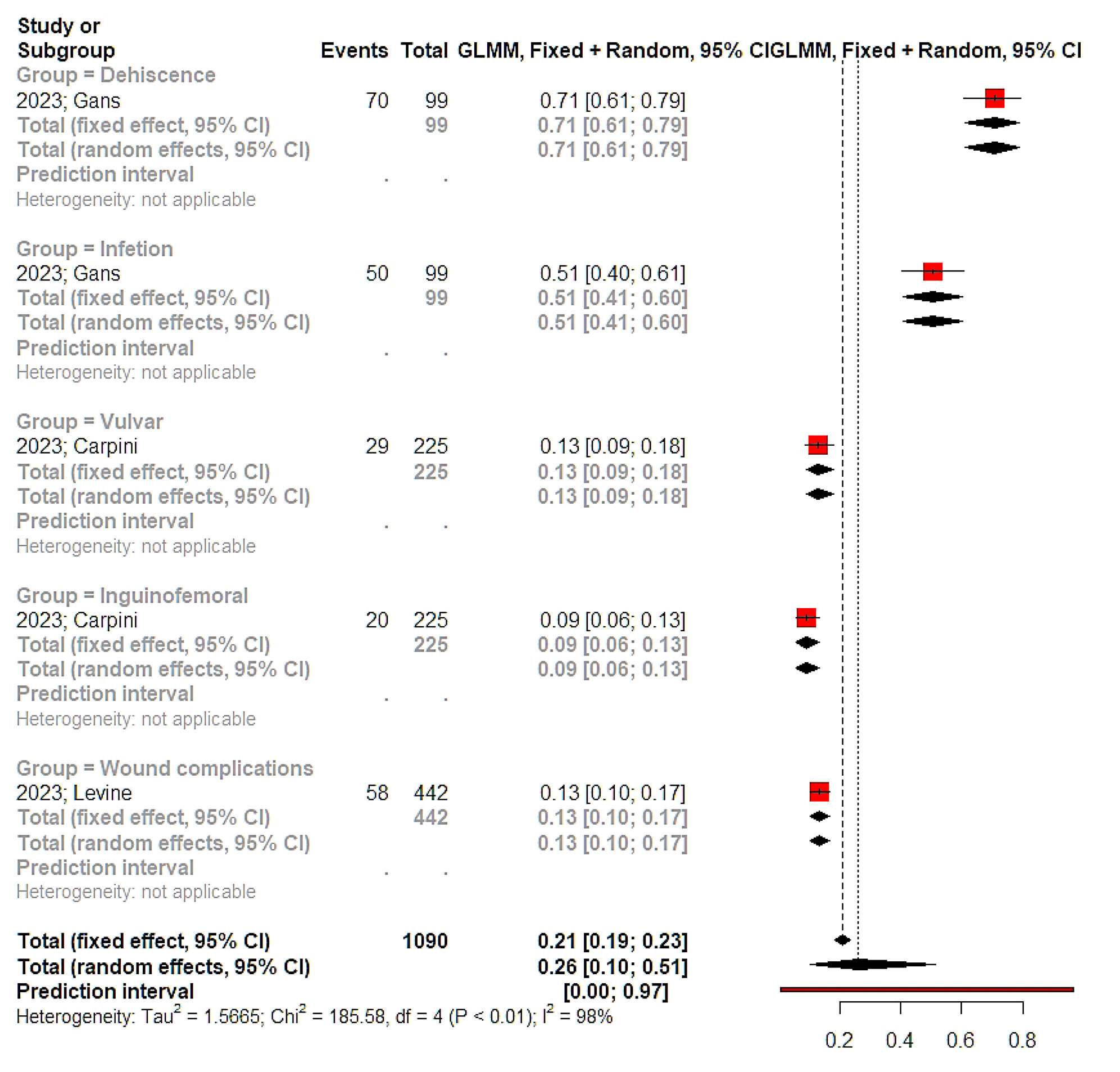

In terms of survival, only two studies reported differences among frail and non-frail patients in terms of overall survival and the overall effect estimate of the meta-analysis indicated the existence of a significantly larger risk of death among frail patients (HR 2.40, 95% CI 1.27, 4.54, Figure 2). The overall incidence of postoperative complications among frail patients was estimated to range between 9 and 79%, however, differences compared to non-frail patients could not be computed due to the absence of relevant data (Figure 3). Some studies adjusted tumor stage and comorbidities, while others did not specify their adjustment factors (Table 2). Only one large study estimated the impact of frailty on postoperative complications after comparing relevant data that were retrieved from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program [22].

Figure 2. Hazards ratio of overall survival. Vertical line = “no difference” point between the two groups. Red squares = hazard ratios of disease free survival of included studies; Horizontal black lines = 95% CI of included studies; Diamond = pooled hazard retrieved from the outcomes of the meta‐analysis and 95% CI for all studies; Horizontal red line = prediction intervals. The weight of included studies is depicted for fixed and random effects model separately.

Figure 3. Proportion meta‐analysis. Vertical lines = mean value of summary effect estimates for the fixed effect and random effect models. Red squares = odds ratios of complications of included studies; Horizontal black lines = 95% CI of odds of complications included studies; Diamonds = pooled odds ratios and 95% CI retrieved from the outcomes of the meta‐analysis for all studies.

In terms of treatment plans, underreporting of frail patients that received optimal treatment was observed. Specifically, Ghebre et al indicated that whereas 72.60% of included patients received adjuvant therapy, only 16.44% received combination chemo- and radiotherapy [4]. Nevertheless, it remains unknown if these patients had indication for adjuvant combination therapy and had downgraded treatment or if they received optimal treatment. In another study Gans et al 63.4% of patients that had de-escalated oncological treatment were frail and that among those 63.6% had some form of postoperative complications within one month from the operation, whereas the possibility of disease recurrence and disease-specific mortality was significantly increased [8].

Discussion

The findings of our study highlight a significant gap in the available data regarding the impact of frailty on the surgical and adjuvant treatment of patients with vulvar cancer, as well as its effect on progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in this patient population. Despite the growing recognition of frailty as a crucial factor in cancer care, the existing body of evidence remains sparse, and the studies that do exist are based on heterogeneous patient groups, often lacking uniformity in patient selection, frailty assessment methods, and treatment protocols. This has a direct impact on decision making during patient consultation as well as the possibility of conducting research on prehabilitation methods that may help decrease the accompanying risks of treatment decisions as well as help increase the ratio of patients receiving necessary treatments. In our meta-analysis we did not observe sufficient evidence to support that frailty indeed affects treatment decisions and results in suboptimal patient care.

Frailty is an established factor that affects survival outcomes of cancer patients, including those suffering from gynecologic malignancies [18, 23]. Several tools have been applied and evaluated in the clinical setting and their diagnostic accuracy seems to be adequate to ensure appropriate patient triage [24] [25]. Of those, the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, the and the are the most prominent scales that have been used in gynecologic oncology [26-28]. It should be noted that frailty does not account only comorbidities but also the gradual exhaustion of the reserve capacity of organ systems which results in a vulnerable state that may affect the perioperative performance of patients, resulting in organ dysfunction. The “Fried frailty criteria” have been proposed that involve low physical activity, poor endurance, weakness, slowness and unintentional weight loss [29].

Frail cancer patients often experience worse survival outcomes due to several factors such as compromised treatment tolerance, increased risk of postoperative complications, delayed recovery and rehabilitation, and immune system impairment. Frailty in colorectal cancer patients was significantly associated with poorer overall survival (HR: 2.11), cancer-specific survival (HR: 4.59), and disease-free survival (HR: 1.46), highlighting the negative impact of frailty on long-term outcomes [30]. Moreover, frailty was strongly linked to increased 30-day mortality (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 3.02, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.77–5.15), adverse discharge disposition (adjusted OR 2.14, 95% CI 1.52–3.02), postoperative complications (adjusted OR 2.39, 95% CI 1.64–3.49), longer-term mortality (unadjusted OR 4.32, 95% CI 2.15–8.67), and longer hospital stays (mean difference 2.30 days, 95% CI 1.10–3.50) [31].

It is important to denote that significant variability is observed among oncology studies concerning the actual definition of frailty resulting in significant heterogeneity and lack of specific consensus that may help direct clinical practice [32]. It should be also noted that frailty frequently coexists with nutritional deficits that severely impact the perioperative course as well as treatment decisions resulting in a multivariate model that, to date, is taken into account based mostly on subjective measures rather than targeted tools [33-35].

Study limitations

The present systematic review summarizes for the first time in the international literature the actual data that correlate frailty with treatment decisions and survival outcomes of vulvar cancer patients. Despite the thorough review of the literature, evidence is extremely scarce, denoting the lack of appropriate focus on this group of patients. It should be noted that most of the included studies underreported the minimum required outcomes to evaluate the impact of frailty in the course of vulvar cancer, including the actual downgrading of surgical and adjuvant therapy as well as the actual complications that were observed following chemo-, radiotherapy as well as perioperative complications. There is an heterogeneity in study populations concerning definitions of frailty, criteria for complications, and surgical procedures assessed. Among the studies included in this systematic review, only two (Ghebre, 2011; Di Donato, 2018) specifically reported the impact of frailty on survival outcomes. However, no comparison group of non-frail patients was available, limiting direct comparisons. Moreover, the impact of frailty on survival outcomes was reported in only two studies and comparison to non-frail patients was available only in a fraction of the studies included in the present systematic review.

Conclusion

Current evidence focusing on the impact of frailty on vulvar cancer patients remains extremely limited and cannot help extrapolate specific clinical implications. While it seems that frail women have significantly decreased overall survival, data are based on outcomes from only 2 studies, whereas treatment decisions and their impact on survival outcomes remain unclear. Future studies should focus on frail populations and compare data to those of non-frail vulvar cancer patients, communicate the potential downgrading of treatment and investigate its impact on morbidity and survival outcomes. Moreover, research focusing on the prehabilitation of these patients is required to evaluate if alternative modes of treatment, for example prehabilitation in combination with neo-adjuvant chemotherapy, may help overcome the obstacle of reduced surgical radicality and, therefore, increase the chances of survival.

Conflict of interest

None for all authors.

Funding

None.

References

- Capria A, Tahir N, Fatehi M. Vulvar Cancer. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Nayha Tahir declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: Mary Fatehi declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.: StatPearls Publishing, Copyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC. 2025.

- Alkatout I, Schubert M, Garbrecht N, Weigel MT, Jonat W, Mundhenke C, et al.: Vulvar cancer: epidemiology, clinical presentation, and management options. Int J Womens Health 2015;7: 305-313.

- Huang J, Chan SC, Fung YC, Pang WS, Mak FY, Lok V, et al.: Global incidence, risk factors and trends of vulvar cancer: A country-based analysis of cancer registries. International Journal of Cancer 2023;153(10): 1734-1745.

- Ghebre RG, Posthuma R, Vogel RI, Geller MA, Carson LF: Effect of age and comorbidity on the treatment and survival of older patients with vulvar cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2011;121(3): 595-599.

- Schuurman MS, Veldmate G, Ebisch RMF, de Hullu JA, Lemmens VEPP, van der Aa MA: Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma in women 80 years and older: Treatment, survival and impact of comorbidities. Gynecologic Oncology 2023; 179: 91-96.

- Oonk MHM, Planchamp F, Baldwin P, Mahner S, Mirza MR, Fischerová D, et al.: European Society of Gynaecological Oncology Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Vulvar Cancer – Update 2023. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2023;33 (7): 1023-1043.

- Rauh-Hain JA, Clemmer J, Clark RM, Bradford LS, Growdon WB, Goodman A, et al.: Management and outcomes for elderly women with vulvar cancer over time. Bjog 2014;121(6): 719-727; discussion 727.

- Gans EA, Portielje JEA, Dekkers OM, de Kroon CD, van Munster BC, Derks MGM, et al.: Frailty and treatment decisions in older patients with vulvar cancer: A single-center cohort study. Journal of Geriatric Oncology 2023;14(2).

- Goede V: Frailty and Cancer: Current Perspectives on Assessment and Monitoring. Clin Interv Aging 2023;18: 505-521.

- Guerard EJ, Deal AM, Chang Y, Williams GR, Nyrop KA, Pergolotti M, et al.: Frailty Index Developed From a Cancer-Specific Geriatric Assessment and the Association With Mortality Among Older Adults With Cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2017;15(7): 894-902.

- Hermann CE, Koelper NC, Andriani L, Latif NA, Ko EM: Predictive value of 5-Factor modified frailty index in Oncologic and benign hysterectomies. Gynecologic Oncology Reports 2022;43: 101063.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al.: The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Journal of clinical epidemiology 2009;62 (10): e1-34.

- Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson j, Welch V, Losos M, et al.: The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Non-Randomized Studies in Meta-Analysis. -2000.

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR: A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Research Synthesis Methods 2010;1(2): 97-111.

- IntHout J, Ioannidis JPA, Borm GF: The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2014;14(1): 25.

- Souza JP, Pileggi C, Cecatti JG: Assessment of funnel plot asymmetry and publication bias in reproductive health meta-analyses: an analytic survey. Reproductive health 2007;4: 3.

- Tang JL, Liu JL: Misleading funnel plot for detection of bias in meta-analysis. Journal of clinical epidemiology 2000;53(5): 477-484.

- Mullen MM, McKinnish TR, Fiala MA, Zamorano AS, Kuroki LM, Fuh KC, et al.: A deficit-accumulation frailty index predicts survival outcomes in patients with gynecologic malignancy. Gynecol Oncol 2021;161(3): 700-704.

- Gans EA, Portielje JEA, Dekkers OM, de Kroon CD, van Munster BC, Derks MGM, et al.: Frailty and treatment decisions in older patients with vulvar cancer: A single-center cohort study. J Geriatr Oncol 2023;14(2): 101442.

- Di Donato V, Page Z, Bracchi C, Tomao F, Musella A, Perniola G, et al.: The age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index as a predictor of survival in surgically treated vulvar cancer patients. J Gynecol Oncol 2019;30(1): e6.

- Delli Carpini G, Sopracordevole F, Cicoli C, Bernardi M, Giuliani L, Fichera M, et al.: Role of Age, Comorbidity, and Frailty in the Prediction of Postoperative Complications After Surgery for Vulvar Cancer: A Retrospective Cohort Study with the Development of a Nomogram. Curr Oncol 2024;32(1).

- Levine MD, Felix AS, Meade CE, Bixel KL, Chambers LM: The modified 5-item frailty index is a predictor of post-operative complications in vulvar cancer: a National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) analysis. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2023;33(4): 465-472.

- Lavecchia M, Marcucci M, Raina P, Jimenez W, Nguyen JMV: Frailty and gynecologic cancer: A cross-sectional analysis of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer 2025: 101642.

- Ferrero A, Massobrio R, Villa M, Badellino E, Sanjinez JOSP, Giorgi M, et al.: Development and clinical application of a tool to identify frailty in elderly patients with gynecological cancers. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer 2024;34(2): 300-306.

- Anic K, Flohr F, Schmidt MW, Krajnak S, Schwab R, Schmidt M, et al.: Frailty assessment tools predict perioperative outcome in elderly patients with endometrial cancer better than age or BMI alone: a retrospective observational cohort study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2023;149 (4): 1551-1560.

- Kumar D, Neeman E, Zhu S, Sun H, Kotak D, Liu R: Revisiting the Association of ECOG Performance Status With Clinical Outcomes in Diverse Patients With Cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2024;22(2 d).

- Hendrix JM, Garmon EH. American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification System. [Updated 2025 Feb 11]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441940/.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR: A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40(5): 373-383.

- Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al.: Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56(3): M146-156.

- Han J, Zhang Q, Lan J, Yu F, Liu J: Frailty worsens long-term survival in patients with colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol 2024;14: 1326292.

- Shaw JF, Budiansky D, Sharif F, McIsaac DI: The Association of Frailty with Outcomes after Cancer Surgery: A Systematic Review and Metaanalysis. Ann Surg Oncol 2022;29(8): 4690-4704.

- Fletcher JA, Logan B, Reid N, Gordon EH, Ladwa R, Hubbard RE: How frail is frail in oncology studies? A scoping review. BMC Cancer 2023;23(1): 498.

- Muszalik M, Gurtowski M, Doroszkiewicz H, Gobbens RJ, Kędziora-Kornatowska K: Assessment of the relationship between frailty syndrome and the nutritional status of older patients. Clin Interv Aging 2019;14: 773-780.

- Hubbard RE, Story DA: Does frailty lie in the eyes of the beholder? Heart Lung Circ 2015;24(6): 525-526.

- Hii TB, Lainchbury JG, Bridgman PG: Frailty in acute cardiology: comparison of a quick clinical assessment against a validated frailty assessment tool. Heart Lung Circ 2015;24(6): 551-556.