Case Report

Kalmantis K, Petsa A, Alexopoulos E, Daskalakis G, Rodolakis A

First Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Alexandra Maternity Hospital, Athens, Greece

Correspondence: Kalmantis Konstantinos, 15 Ifigenias str P. Faliro, Athens Greece, Tel: 0030 6972839327, Email: kkalmantis@hotmail.com

Abstract

Introduction: Ovarian cysts occur in 3% of pregnancies. Usually, they do not have clinical symptoms and are found accidentally during the ultrasound screening performed in the 1st trimester of pregnancy. Materials and Methods: Articles were identified through electronic databases; no date or language restrictions were placed; relevant citations were hand searched. The search was conducted using the following terms: ovarian tumors, ovarian cyst, pregnancy, management, and outcome. Discussion: Vast majority is benign; these are functional cysts which resolve in the 2nd trimester. Discrimination of these cysts can be made by color ultrasonography. Ultrasound examination will provide useful information on the size, composition and nature of the tumor, in order to avoid unnecessary surgical interventions during pregnancy. Conclusions: Management of cysts in pregnancy should mainly include a detailed evaluation, through color sonography, based on specific I.O.T.A. criteria, and appropriate treatment should be decided, based on the main purpose of providing healthcare to the pregnant woman and ensuring successful outcome of the pregnancy.

Keywords: ovarian cyst, pregnancy, ultrasound evaluation, sonographic features, management, outcome.

Introduction

Finding an ovarian tumor during pregnancy accounts for about 3%1. Usually, these cysts do not have clinical symptoms and are found accidentally during the ultrasound screening performed in the 1st trimester of pregnancy2. The most common cyst in pregnancy is the persistent corpus luteum, which in 85% of cases resolves spontaneously in the early of the 2nd trimester3-5 Cysts that persist beyond the 16th week of pregnancy are not functional and require further investigation. Rarely these are complicated by pain, torsion, and rupture and create noisy symptoms and bleeding6. Finally, the incidence of ovarian cancer in pregnant women aged between 18 and 39 years old, is 1-8 per 100,000 women7-8.

Before the application of ultrasound in clinical practice, diagnosis of ovarian cysts in pregnancy was made by physical examination, especially in cases of pregnant women with symptoms such as abdominal pain or palpable mass. In these cases, immediate surgical intervention was preferred in order to avoid complications. In recent decades, the use of ultrasound changed the management and more information was available to predict the nature of a cyst in pregnancy. The main purpose was to identify and distinguish the cases of pregnant women that require surgical intervention4,9,10.

Materials and Methods

The purpose of this paper is to provide a complete review for ovarian cysts in pregnancy as a guide for the appropriate management. The authors researched through electronic databases articles concerning this specific subject. No date or language restrictions were placed; relevant citations were hand searched. The search was conducted using the following terms: ovarian tumors, ovarian cyst, pregnancy, management, and outcome.

Discussion

Cysts in pregnancy are divided into benign and malignant. The most common benign ovarian tumors are functional cysts, followed by dermoid cysts, cystadenomas, endometriomas, and finally peritoneal and paraovarian cysts. Malignant ovarian tumors include non-epithelial (germ cell-sex cord) and epithelial tumors (borderline ovarian tumors, invasive ovarian tumors).

Cysts are diagnosed by ultrasound, where high diagnostic accuracy allows discrimination of ovarian tumors in benign and malignant7,9,10,11.

Various studies and algorithms have been reported in literature, in order to assess the possibility of malignancy of an ovarian tumor during pregnancy 9,10-17. International Ovarian Tumor Analysis group (I.O.T.A.) described the morphological characteristics and angiogenesis of ovarian tumors (“Simple rules”), to determine their nature18, 19. According to I.O.T.A., the characteristics of benign tumors are the following: 1) unilocular cyst of low echogenicity, 2) presence of solid components (diameter <7mm), 3) acoustic shadowing, 4) multilocular cyst, with smooth surface and a major diameter of <100mm, 5) no blood flow, while the malignant characteristics are: 1) solid tumor with irregular surface, 2) ascites, 3) more than 4 pappilary projections, 4) solid multilocular tumor with major diameter> 100mm and 5) strong blood flow. If there are one or more benign characteristics, the tumor is defined as benign. If there are one or more malignant characteristics, then the tumor is classified as malignant. If none of the above features exist or if malignant and benign characteristics coexist, then the tumor cannot be classified.

In pregnancy, frequently encountered unilocular cysts of low echogenicity, without vascularization, with a size smaller than 50mm, with smooth surface. They remain asymptomatic and tend to regress during pregnancy. Transvaginal ultrasound color flow imaging, based on specific rules of I.O.T.A. (Simple rules) can help in the diagnosis of a cyst in pregnancy18, 19. The sonographic features of cysts occurring in pregnancy are listed in Table 1.

Recent studies have reported the usefulness of color ultrasound (Doppler), in the evaluation of cysts in pregnancy. The pulsatility index (PI), and the vascular resistance index (RI) have low values in malignancies, as the vessels of the tumors lack muscular layer. Thereby they present low resistances20, 21. Shah et al, have reported high sensitivity and specificity in the detection of malignant tumors with PI <1 (sensitivity 93%, specificity 93%) and RI <0.6 (sensitivity 83%, specificity 93%)22.

Nevertheless, there is a significant overlap rate between RI and RI in benign and malignant ovarian tumors. Especially in pregnancy, where increased blood flow of the uterus and hemodynamic changes from all three trimesters of the pregnancy affect even more RI and PI values21. Also, three-dimensional color ultrasound provides additional information to distinguish cysts, from the first trimester of the pregnancy, without harming the fetus and hassling the pregnant woman23, 24.

MRI is safely used in the 2nd – 3rd trimester of pregnancy. Its role is mostly assistive (when the ultrasound diagnosis is uncertain or there are suspicious sonographic findings)25. It can accurately distinguish the content of the tumor (liquid or solid), displays the exact origin of pelvic formations and controls in detail the existence of vascularization26-29.

Correlation between tumor markers and pregnancy is unclear. Ca–125 is most frequently used. It is a glycoprotein that increases in primary ovarian carcinoma, as well as in benign conditions such as endometriosis, uterine fibroids, pelvic inflammation, menstruation and pregnancy30-32. Particularly during the 1st and 3rd trimester, increased amounts of Ca–125 are produced from amnion and decidua. This marker is estimated mainly when its value is greater than 100IU/ml, while its main use is disease progression or response to therapy33, 34.

Management of cysts in pregnancy

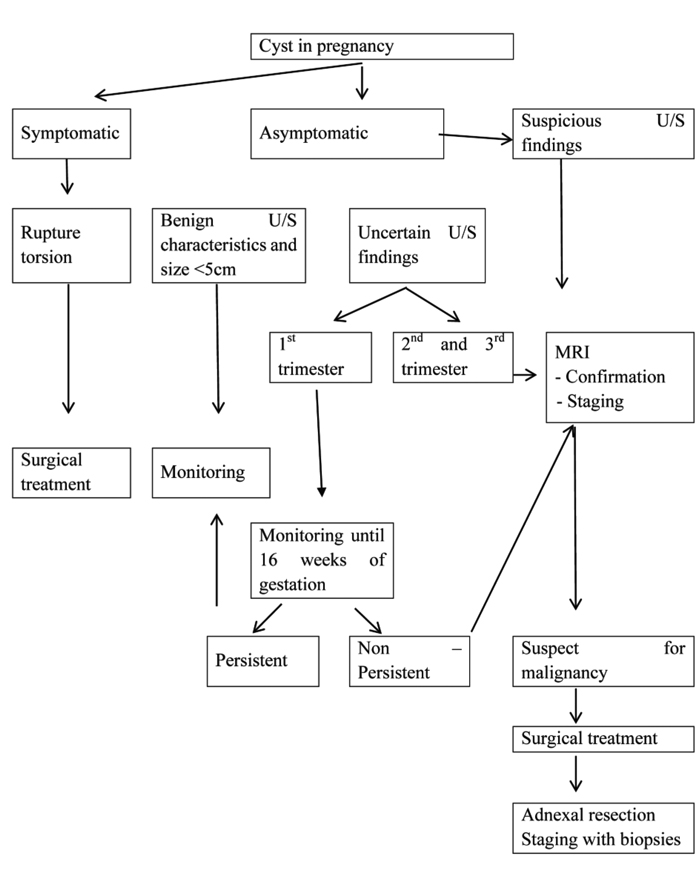

The decision whether a cyst in pregnancy will be managed conservatively or surgically depends on the sonographic features and the size of the cyst35. Initially, conservative management of cysts is recommended, with regular monitoring, as 71% of them will be absorbed36, 37. According to the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, simple, unilateral, unilocular ovarian cysts <5cm have a low risk of malignancy and can be treated conservatively38. Also, regular ultrasound examination assists early detection of progressive changes in the size and morphology of tumors39. In asymptomatic tumors, without signs of malignancy, which are detected in the 1st trimester, re-examination is recommended at 16 weeks of gestation. If this does not persist and remains stable, ultrasound re-examination is recommended at 6-8 weeks postpartum 13. In case that the cyst persists or increases in size, after 16 weeks of gestation, and there are equivocal or suspicious sonographic findings for malignancy, MRI in the lower abdomen and surgical intervention are recommended. Moreover, surgical intervention is required when a complication occurs, such as rupture, torsion, and bleeding (Figure 1) 13, 40-42. Second trimester, between 16 and 23 weeks of gestation, is considered ideal for surgical intervention, since the risk for spontaneous abortion of 1st trimester and preterm delivery of 3rd trimester is reduced43, 44.

Figure 1. Management of cyst in pregnancy

Conclusions

Cysts occur in 3% of pregnancies. Vast majority is benign; these are functional cysts which resolve in the 2nd trimester. Discrimination of these cysts can be made by color ultrasonography. Ultrasound examination will provide useful information on the size, composition and nature of the tumor, in order to avoid unnecessary surgical interventions during pregnancy. Features, such as tumor size> 5cm, heterogeneous echostructure, irregular surface, presence of wall abnormalities, presence of solid components with vascularization, raise strong suspicion of malignancy.

Color three-dimensional ultrasonography significantly increases diagnostic accuracy, while MRI has a complementary-supportive role, especially when there are suspicious sonographic findings. Tumor markers are not reliable in investigating cysts in pregnancy, due to their low specificity.

Cysts in pregnancy should be evaluated in detail, through color sonography, based on specific I.O.T.A. criteria, and appropriate treatment should be decided, based on the main purpose of providing healthcare to the pregnant woman and ensuring successful outcome of the pregnancy.

References

1. Goffinet F.[Ovarian cysts and pregnancy].J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2001 Nov;30(1 Suppl):S100-8.

2. Sherard GB 3rd, Hodson CA, Williams HJ, Semer DA, Hadi HA, Tait DL. Adnexal masses and pregnancy: a 12-year experience. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Aug;189(2):358-62; discussion 362-3.

3. Nelson MJ, Cavalieri R, Graham D, Sanders RC. Cysts in pregnancy discovered by sonography. J Clin Ultrasound. 1986 Sep;14(7):509-12.

4. Hogston P, Lilford RJ. Ultrasound study of ovarian cysts in pregnancy: prevalence and significance.Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1986 Jun;93(6):625-8.

5. Platek DN, Henderson CE, Goldberg GL. The management of a persistent adnexal mass in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995 Oct;173(4): 1236-40.

6. Whitecar MP, Turner S, Higby MK. Adnexal masses in pregnancy: a review of 130 cases undergoing surgical management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Jul;181(1):19-24.

7. Hoover K, Jenkins TR. Evaluation and management of adnexal mass in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Aug;205(2):97-102.

8. Runowicz CD, Brewer M. Goff B, Section Editor. Adnexal mass in pregnancy, 2016.

9. Glanc P, Salem S, Farine D. Adnexal masses in the pregnant patient: a diagnostic and management challenge. Ultrasound Q. 2008 Dec;24(4):225-40.

10. Leiserowitz GS. Managing ovarian masses during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2006 Jul;61(7):463-70.

11. Usui R, Minakami H, Kosuge S, Iwasaki R, Ohwada M, Sato I. A retrospective survey of clinical, pathologic, and prognostic features of adnexal masses operated on during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2000 Apr;26(2):89-93.

12. Bignardi T, Condous G. The management of ovarian pathology in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2009 Aug;23(4):539-48.

13. Aggarwal P, Kehoe S. Ovarian tumours in pregnancy: a literature review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011 Apr;155(2):119-24.

14. Bromley B, Benacerraf B. Adnexal masses during pregnancy: accuracy of sonographic diagnosis and outcome. J Ultrasound Med. 1997 Jul;16(7):447-52; quiz 453-4.

15. Knudsen UB, Tabor A, Mosgaard B, Andersen ES, Kjer JJ, Hahn-Pedersen S, Toftager-Larsen K, Mogensen O. Management of ovarian cysts. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004 Nov;83(11):1012-21.

16. Levine D, Barbieir RL (ed). Up to date 2015. Sonographic differentiation of benign versus malignant adnexal masses.

17. Telischak NA, Yeh BM, Joe BN, Westphalen AC, Poder L, Coakley FV. MRI of adnexal masses in pregnancy.AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008 Aug;191(2):364-70.

18. Timmerman D, Valentin L, Bourne TH, Collins WP, Verrelst H, Vergote I; International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) Group. Terms, definitions and measurements to describe the sonographic features of adnexal tumors: a consensus opinion from the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) Group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000 Oct;16(5):500-5.

19. Timmerman D, Ameye L, Fischerova D, Epstein E, Melis GB, Guerriero S, Van Holsbeke C, Savelli L, Fruscio R, Lissoni AA, Testa AC, Veldman J, Vergote I, Van Huffel S, Bourne T, Valentin L. Simple ultrasound rules to distinguish between benign and malignant adnexal masses before surgery: prospective validation by IOTA group.BMJ. 2010 Dec 14;341:c6839.

20. Fleischer AC, Cullinan JA, Jones HW 3rd, Peery CV, Bluth RF, Kepple DM. Serial assessment of adnexal masses with transvaginal color Doppler sonography. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1995;21(4):435-41.

21. Wheeler TC, Fleischer AC. Complex adnexal mass in pregnancy: predictive value of color Doppler sonography. J Ultrasound Med. 1997 Jun;16(6): 425-8.

22. Shah D, Shah S, Parikh J, Bhatt C J, Vaishnav K, Bala D V. Doppler ultrasound: a good and reliable predictor of ovarian malignancy. J Obstet Gynecol India 2013;63(3):186-189

23. Testa AC, Ajossa S, Ferrandina G, Fruscella E, Ludovisi M, Malaggese M, Scambia G, Melis GB, Guerriero S. Does quantitative analysis of three- dimensional power Doppler angiography have a role in the diagnosis of malignant pelvic solid tumors? A preliminary study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Jul;26(1):67-72.

24. Kalmantis K, Iavazzo C, Anastasiadou V, Antsaklis A. The role of 3-dimensional power Doppler imaging in the assessment of ovarian teratoma in pregnancy: a case report. Case Rep Med. 2011; 2011:896396.

25. Patenaude Y, Pugash D, Lim K, Morin L; Diagnostic Imaging Committee., Lim K, Bly S, Butt K, Cargill Y, Davies G, Denis N, Hazlitt G, Morin L, Naud K, Ouellet A, Salem S; Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. The use of magnetic resonance imaging in the obstetric patient. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2014 Apr;36(4):349-63.

26. Curtis M, Hopkins MP, Zarlingo T, Martino C, Graciansky-Lengyl M, Jenison EL. Magnetic resonance imaging to avoid laparotomy in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1993 Nov;82(5):833-6.

27. Buist MR, Golding RP, Burger CW, Vermorken JB, Kenemans P, Schutter EM, Baak JP, Heitbrink MA, Falke TH. Comparative evaluation of diagnostic methods in ovarian carcinoma with emphasis on CT and MRI. Gynecol Oncol. 1994 Feb;52(2):191-8.

28. Yakasai IA, Bappa LA. Diagnosis and management of adnexal masses in pregnancy. J Surg Tech Case Rep. 2012 Jul;4(2):79-85.

29. Araujo Júnior E, Sun SY, Campanharo FF, Nacaratto DC, Nardozza LM, Mattar R, Habib VV, Moron AF. Diagnosis of ovarian metastasis from gestational trophoblastic neoplasia by 3D power Doppler ultrasound and dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging: case report. Case Rep Oncol. 2012 May;5(2):359-66.

30. Bast RC Jr, Feeney M, Lazarus H, Nadler LM, Colvin RB, Knapp RC. Reactivity of a monoclonal antibody with human ovarian carcinoma. J Clin Invest. 1981 Nov;68(5):1331-7.

31. Bast RC Jr, Klug TL, St John E, Jenison E, Niloff JM, Lazarus H, Berkowitz RS, Leavitt T, Griffiths CT, Parker L, Zurawski VR Jr, Knapp RC. A radioimmunoassay using a monoclonal antibody to monitor the course of epithelial ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 1983 Oct 13;309(15):883-7.

32. Jacobs IJ, Fay TN, Yovich J, Stabile I, Frost C, Turner J, Oram DH, Grudzinskas JG. Serum levels of CA 125 during the first trimester of normal outcome, ectopic and anembryonic pregnancies. Hum Reprod. 1990 Jan;5(1):116-22.

33. Mc Carthy A. 7th ed. United States: Blackwell publishing: 2007. Miscellaneous Medical Disorders Dewhurst’s textbook of Obstetrics and Gynaecology: 283-8.

34. Aslam N, Ong C, Woelfer B, Nicolaides K, Jurkovic D. Serum CA125 at 11-14 weeks of gestation in women with morphologically normal ovaries. BJOG. 2000 May;107(5):689-90.

35. Caspi B, Levi R, Appelman Z, Rabinerson D, Goldman G, Hagay Z. Conservative management of ovarian cystic teratoma during pregnancy and labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000 Mar;182(3):503-5.

36. Schmeler KM, Mayo-Smith WW, Peipert JF, Weitzen S, Manuel MD, Gordinier ME. Adnexal masses in pregnancy: surgery compared with observation. Obstet Gynecol. 2005 May;105(5 Pt 1):1098-103.

37. Leiserowitz GS. Managing ovarian masses during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2006 Jul;61(7):463-70.

38. RCOG. Ovarian cyst in post-menopausal women (Green-top 34). In: Green top Guidelines: RCOG: 2003.

39. Zanetta G, Mariani E, Lissoni A, Ceruti P, Trio D, Strobelt N, Mariani S. A prospective study of the role of ultrasound in the management of adnexal masses in pregnancy. BJOG. 2003 Jun;110(6):578-83.

40. Mavromatidis G, Sotiriadis A, Dinas K, Mamopoulos A, Rousso D. Large luteinized follicular cyst of pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Oct;36(4):517-20.

41. Shah K, Anjurani S, Ramkumar V, Bhat P, Urala M. Ovarian mass in pregnancy: a review of six cases treated with surgery. Internet J Gynecol Obstet, 2013;14 (2)

42. Fujishita A, Masuzaki H, Nakajima H, Ishimaru T, Yamabe T. The evaluation of ovarian tumor associated with pregnancy by the ultrasonographical method and serum CA125 levels. Nihon Sanka Fujinka Gakkai Zasshi. 1994 Sep;46(9):875-82.

43. Agarwal N, Parul, Kriplani A, Bhatla N, Gupta A. Management and outcome of pregnancies complicated with adnexal masses. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2003 Jan;267(3):148-52.

44. Mazze RI, Källén B. Reproductive outcome after anesthesia and operation during pregnancy: a registry study of 5405 cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989 Nov;161(5):1178-85.

Received 23-8-2017

Revised 20-9-2017

Accepted 6-10-2017